After World War II, the beauty industry boomed, and opening a beauty parlor in one’s community attracted increasing numbers of enterprising women. In 1946, the borough of Manhattan alone boasted 2,175 beauty parlors, and even before the postwar boom, these mostly woman-owned small businesses cumulatively grossed annual national revenues exceeding $116 million. Sue Ying Moy’s beauty parlor stood out in a neighborhood full of barbershops and male-owned businesses. Through her own efforts, Moy navigated recently set up English-language-only bureaucracy to open her own salon in New York Chinatown in 1948 and successfully ran it for more than a decade. In 1935, the New York State Senate had approved a bill establishing state regulation of beauty parlors and cosmetologists and had set up an English-language state licensing and examination system that functionally excluded non-English-speakers. Beauty parlor proprietors had been opposing such proposals since at least 1927, fearing that state regulation would open the way for mostly male barbers, whom the 1935 bill notably exempted, “to dominate the hairdressing business.”

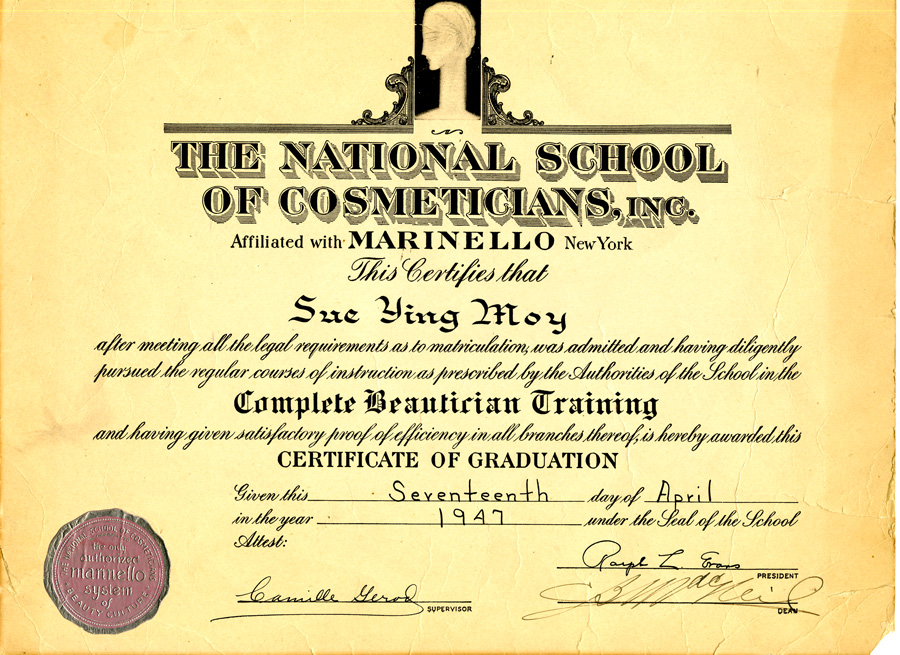

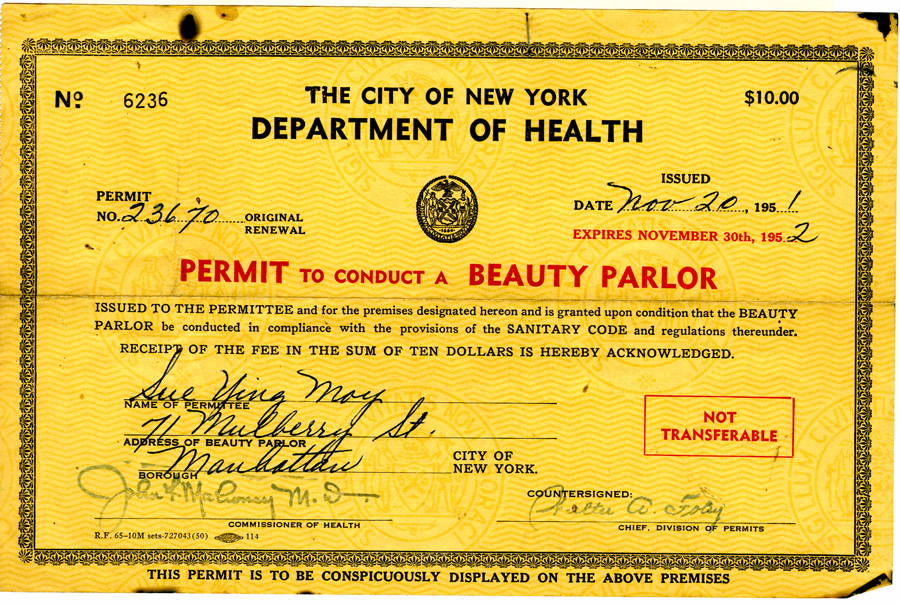

We do not have photographs of her beauty parlor but one can perhaps imagine that as more Chinese women immigrated to the US as war brides, it would have provided a space for Chinatown’s women to not only get the latest beauty trends and treatments, but also socialize, share information, and make memories as men did in neighborhood barbershops. Documents that family members donated to MOCA’s archives show that in 1947, Moy graduated from a nationally accredited cosmetology school and completed the requisite formal training to obtain a license to conduct her business. She subsequently signed a lease of $75 a month for storefront space at 71 Mulberry from Park Bayard Realty, and until 1960, paid the NYC Department of Health a yearly sum of $10 for a permit to keep her establishment open. Our only photograph possibly captures Moy, unidentified, with students from her school in China at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. No additional information accompanies the photograph but it suggests that in the years immediately after she closed her beauty parlor, she may have participated in a people-to-people exchange that China began to initiate with Western countries in the 1960s and 1970s. The short bob cuts and bouffant hair sported by women in the photo—popular at the time—were styles that were less easy to achieve by oneself at home and would have occasioned a visit to a salon.