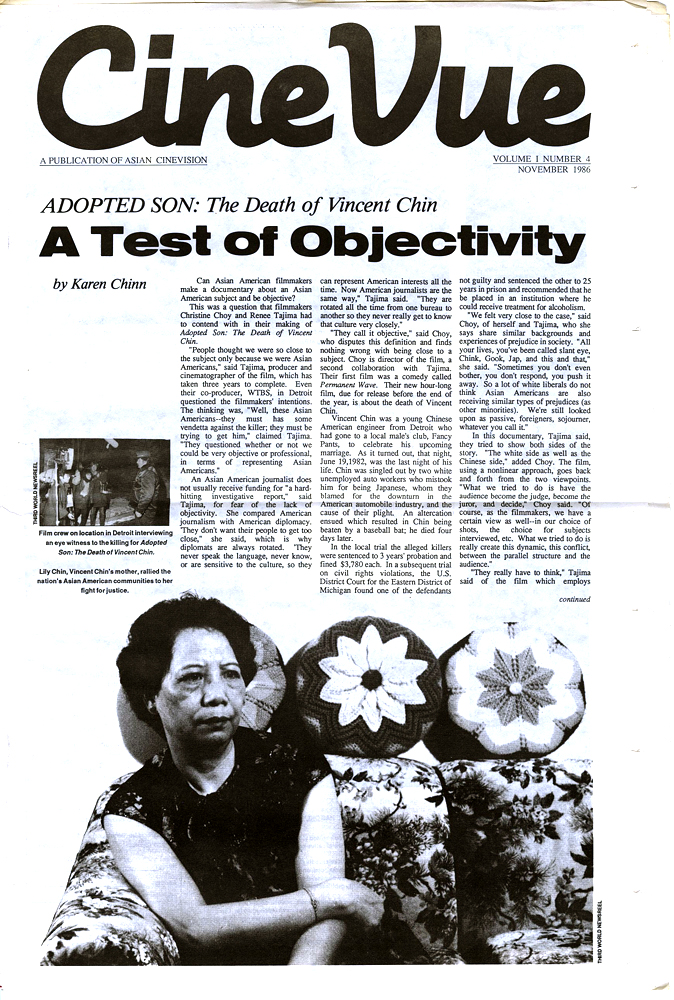

Lily Chin, featured on the cover of this November 1986 CineVue issue, became the face of a nationwide campaign for justice after a Michigan county circuit judge sentenced the men who murdered her son, Vincent Chin, to only three years probation and a $3,000 fine. In defense of his sentence, Judge Charles Kaufman insisted, “These aren’t the kind of men you send to jail. We’re talking here about a man who’s held down a responsible job for 17 or 18 years, and his son is employed and is a part-time student. You don’t make the punishment fit the crime, you make the punishment fit the criminal.” The sentence, which clearly disregarded Lily Chin’s immense loss and devalued Vincent Chin’s life (pricing its taking at a mere $3000), stunned and outraged Asian Americans, and mobilized many around her subsequent pursuit of justice at the federal level. However, although a federal grand jury convicted Ronald Ebens in the first civil rights case tried on behalf of an Asian American in U.S. history, an appeals court reversed the decision and a retrial cleared him of all charges. His accomplice in the murder, Michael Nitz, was found not guilty on both counts.

Helen Zia, an activist in the legal case, explained that the federal case revolved around the question of whether the murder had been racially motivated, and unfortunately, the second jury in Cincinnati which acquitted Ebens didn’t have an understanding of the racism that Asian Americans in Detroit faced in the 1980s. Racial slurs witnesses heard Ebens and Nitz direct at Chin evidenced that they blamed Japan, and by mistaken association, Chin, for the decline of Detroit’s auto industry, long a ticket to middle class security for white American workers. But even though Asian Americans were increasingly targets of scapegoating and violence during this decade, their experiences were rendered largely invisible by a model minority myth predominating enough to lead a white jury to believe the defendants’ claim that their brutal beating and murder of Vincent was not a hate crime.

In this CineVue issue’s interview on the making of their documentary about the Vincent Chin case, initialed titled “Adopted Son” but released in 1987 as “Who Killed Vincent Chin?,” co-directors Christine Choy and Rene Tajima-Peña described having to work within the constraints of this master narrative even while attempting to dislodge it. At the time of the interview, they had completed up to 90% of the film but ran out of funding and had had to cobble together various grants because there was not a lot of institutional support for Asian American filmmakers and the making of this kind of film. And even though a core problem highlighted by the rulings on the case was the dearth of consideration of Asian American humanity and perspectives, Choy and Tajima-Peña felt pressured to adhere to the journalism profession’s ethics of objectivity, likely resulting in their choice to present and juxtapose opposing perspectives, including not only those of Lily Chin and other Asian American activists but also those of Ebens and Nitz. CineVue, which started publication in that very year (1986), and the organization which published it, Asian CineVision, sought to address these very gaps and issues, offering a platform to promote Asian American voices and stories told through film.

Today, both Choy and Tajima-Peña consciously mentor younger generations of Asian American filmmakers, and the painstaking research and eyewitness interviews they conducted for their first collaborative film—archived at MOCA—continue to serve as an important primary source for journalists and scholars.