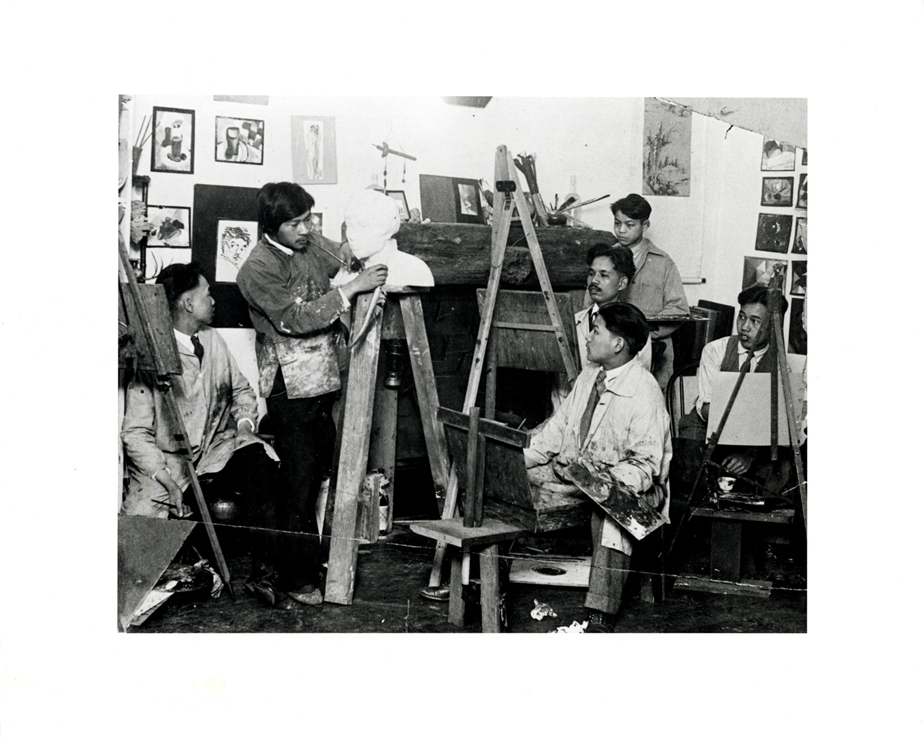

Scant historical evidence of possibly the first Chinese immigrant artist collective, the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club, include this one known existing photograph, taken at their cramped studio at 150 Wetmore Place in San Francisco Chinatown circa the year of their formation in 1926. During the 1920s decade, art clubs and small independent galleries flourished in the city, however, xenophobia, culminating in the 1924 Immigration Act which completely barred immigration from Asia, made it so that only at the Chinese Revolutionary Artists’ Club could Chinese aspiring artists find welcome and creative outlet.

Membership fluctuated over the decade and a half of the club’s existence and most names remain unknown, but members were likely men in their late teens and early twenties, as captured in the photograph above. (The club’s lone female member, Mrs. Eva Fong Chan, was granted membership in the early 1930s, shortly after the group hosted a visit by famed Mexican muralist Diego Rivera). Art scholar and critic Anthony W. Lee posits that the photograph was likely staged (after all, who would risk painting in one’s expensive suit?), and shows Yun Gee, the group’s most famous member, using a bust to give a lesson on modernist oil painting to attentive club members seated in front of their respective easels. Their vests and ties belied their likely working-class status and day jobs as servants, cooks, dishwashers, and launderers—the professions allowed Chinese of little means during this era. Members pooled their meager wages to afford the precious paints and other communally shared art supplies, and painted the modest subjects at hand—“the street scenes, people and goods of Chinatown”—on cheap paperboard rather than expensive primed canvas. Except for modernist painter Yun Gee, who left for Paris in 1927 and often broke barriers by being the first Asian to show in many museums and galleries, no other members were able to achieve mainstream success within the constraints of anti-Chinese racism in the U.S. However, in the collectivity of the club they found a safe space to dream and be more than the hostile world outside of Chinatown allowed them, and some went on to teach younger generations of aspiring Chinese American artists within their community.