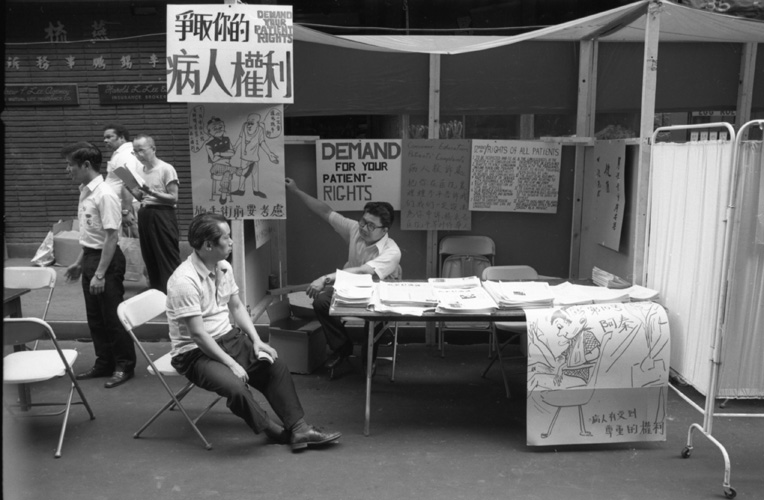

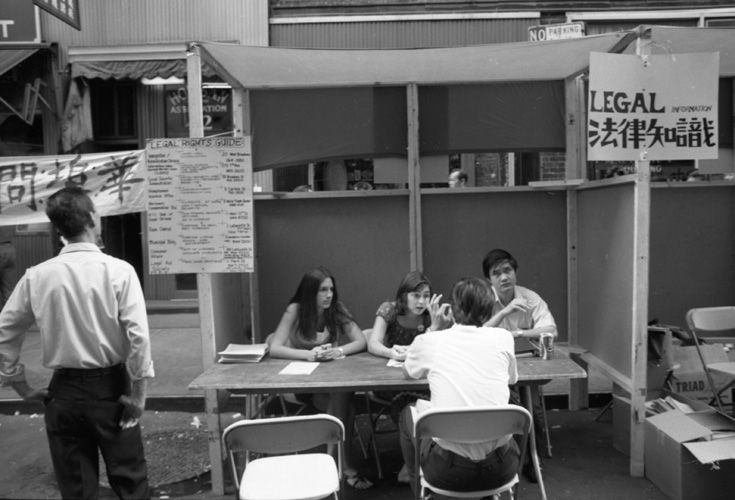

In the summer of 1973, banners rallying the community to “Unite & Fight for Our Rights!” stretched high above Mott and Pell Streets, as Chinatown’s streets transformed into a powerful space for activism and care during the Chinatown Street Fair. Inspired by the Black Panthers and other grassroots programs melding social services, political empowerment and education, fair organizers set up booths all along Mott and Pell Streets, where community members could receive free health screenings, as well as information about their rights as patients, workers, and tenants.

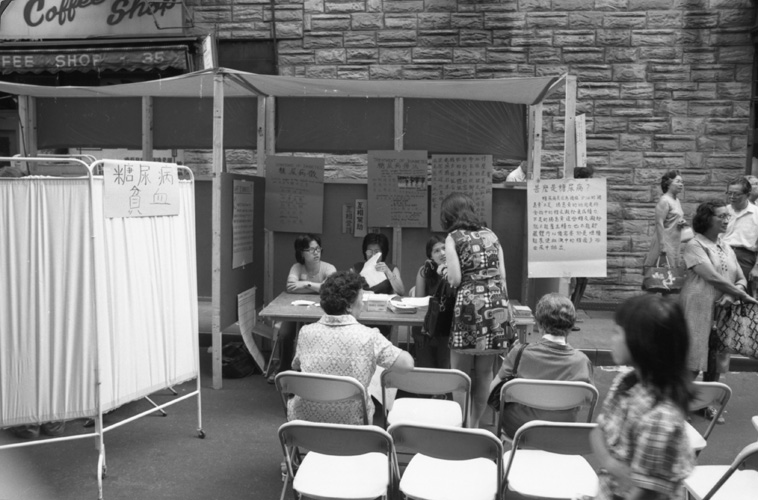

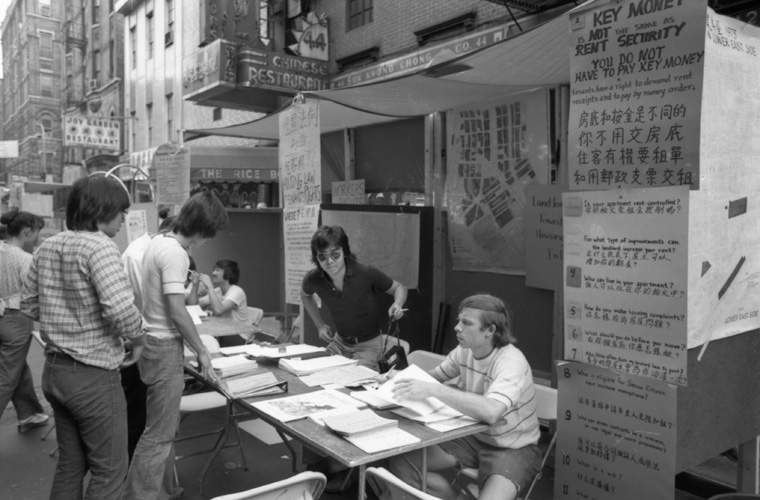

Bilingual posters displayed at the tenants’ rights booth educated residents about housing law and encouraged them to fight against unjust practices. For example, as the influx of new immigrants brought pressure to Chinatown’s already limited housing stock, one poster addressed the pervasive practice of landlords charging new tenants “key money”—sometimes amounting to several months’ rent—before allowing them to move into an apartment. At the women’s health booth, volunteers talked to women about the importance of getting breast exams and encouraged them to register for mammograms. At the nutrition booth, Virginia Tan, a nutritionist with the Dairy Council of Metropolitan New York, was on hand for questions and consultations. She was aided in her explanations by posters illustrated with ingredients of Chinese cuisine such as bok choy, tofu, cellophane noodles, and pork sausages to represent the four basic food groups. More than two hundred volunteers—many of them college students who could help serve as Chinese language interpreters—assisted medical professionals at the various booths in taking people’s blood pressure, administering Tine tests for tuberculosis, and collecting blood samples to send to Bellevue Hospital to check for diabetes, high lead levels in children and other conditions.

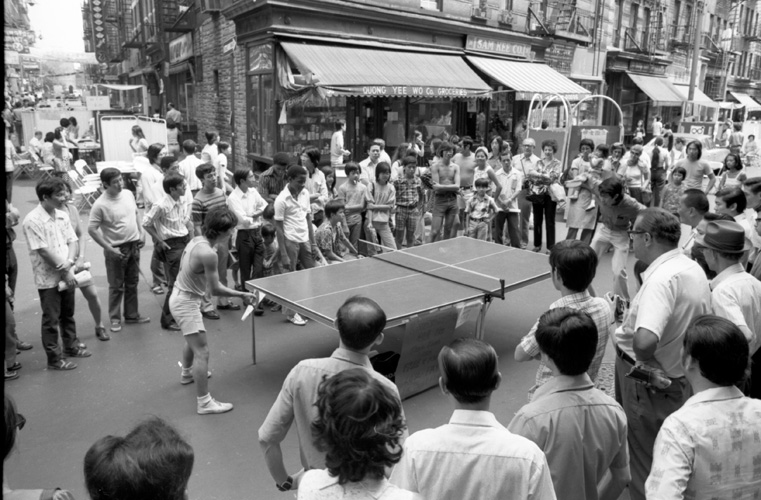

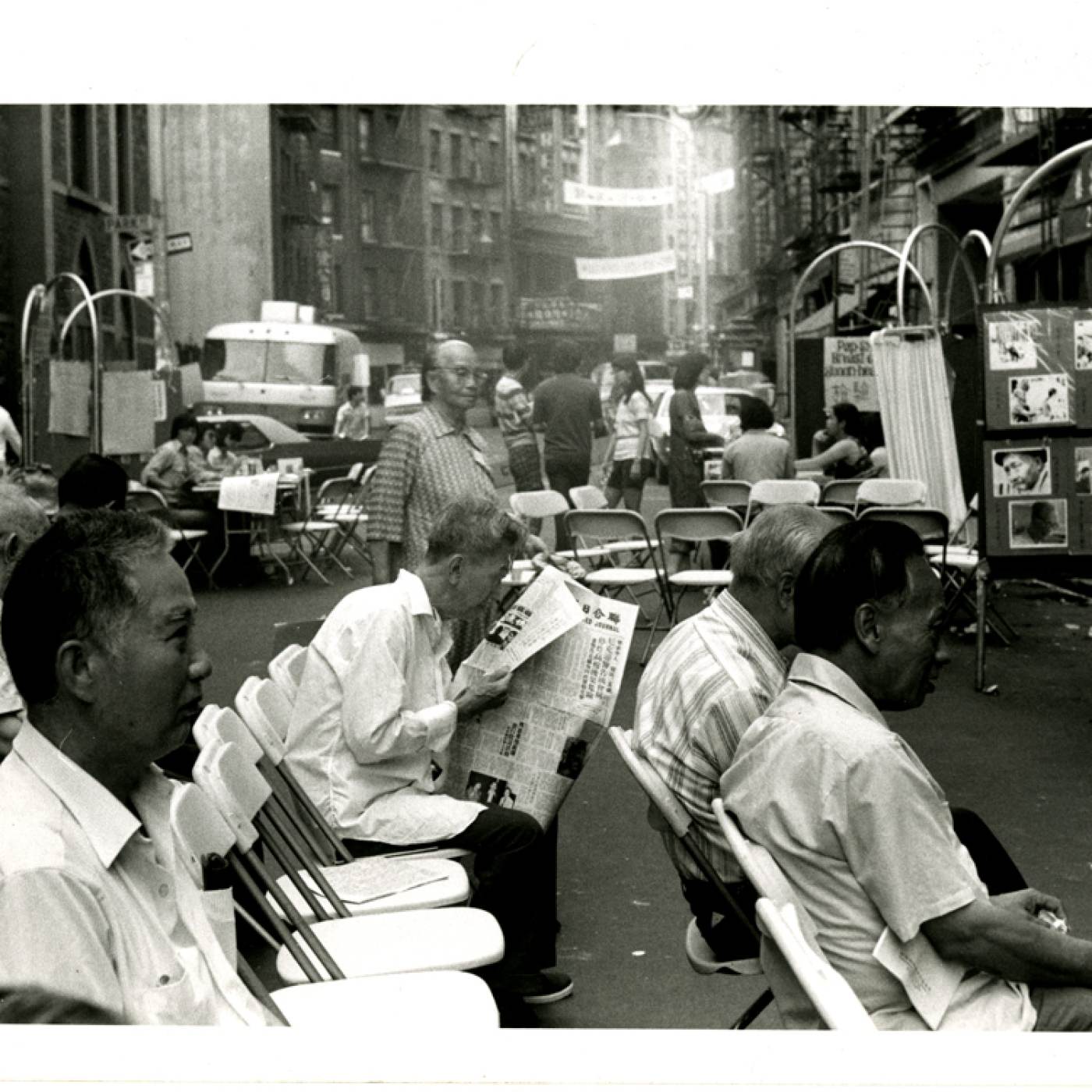

Parents visiting the booths could drop their young children off to play and be looked after at a mini day care center, while seniors could sip cold drinks at a designated seating area and watch taped interviews of fellow elders talking about their experiences in America. At 50 cents per ping pong game, to be paid by the loser, fairgoers could also challenge each other at a ping pong table in the middle of the street that attracted considerable spectator attention and helped raise funds for the fair.

The 1973 Chinatown Street Fair built on the success of the first Chinatown Health Fair organized in 1971 by Dr. Thomas Tam and other Asian American activists. Over the course of this first health fair, more than 2,500 attendees received free medical screenings. Of these, two-thirds indicated that they lacked health insurance. Using the momentum and community support galvanized by the fair, Dr. Tam pushed for Chinese patient advocates and interpreters to be hired at the nearby Gouverneur Hospital and helped establish a more permanent Chinatown Health Clinic, which continues to meet the community’s need for affordable, language-accessible, quality healthcare as today’s Charles B. Wang Community Health Center.