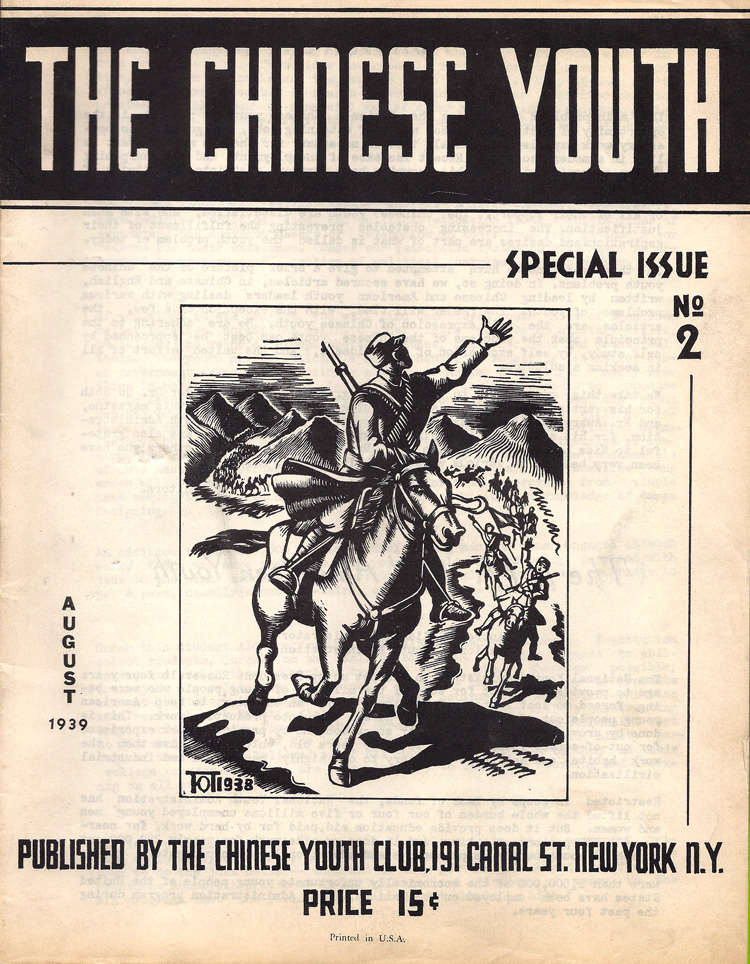

When Japan invaded Guangzhou in 1938, many Chinese parents living in the United States began to worry for the children they left at home. This fear of Japanese aggression resulted in an influx of Chinese youth to many cities across the United States by the late 1930’s. Empowered by China’s now-unified front against Japan, Chinese youths had the freedom in the United States to protest the Japanese invasion—and did so through creating Chinese Youth National Salvation Club, which also became known as the Chinese Youth Club (CYC).

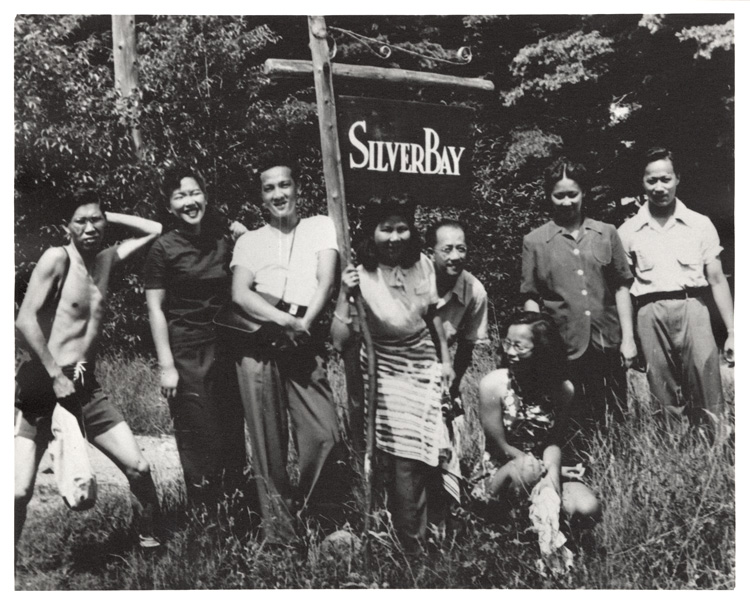

The youth organization supported the Chinese war effort against Japan through lectures, photography exhibitions, film screening, and various performances. The CYC even branched out into more mainstream American political movements, like the May First Labor Day Parades, New York City boycotts of Japanese silk, and protests at the Brooklyn waterfront over the shipment of scrap metal to Japan. Its heyday continued into the U.S. and China’s alliance, but once American presidents started suspecting Chinese clubs for communist activity during the Cold War, membership to centers like the Chinese Youth Club became dangerous and declined.