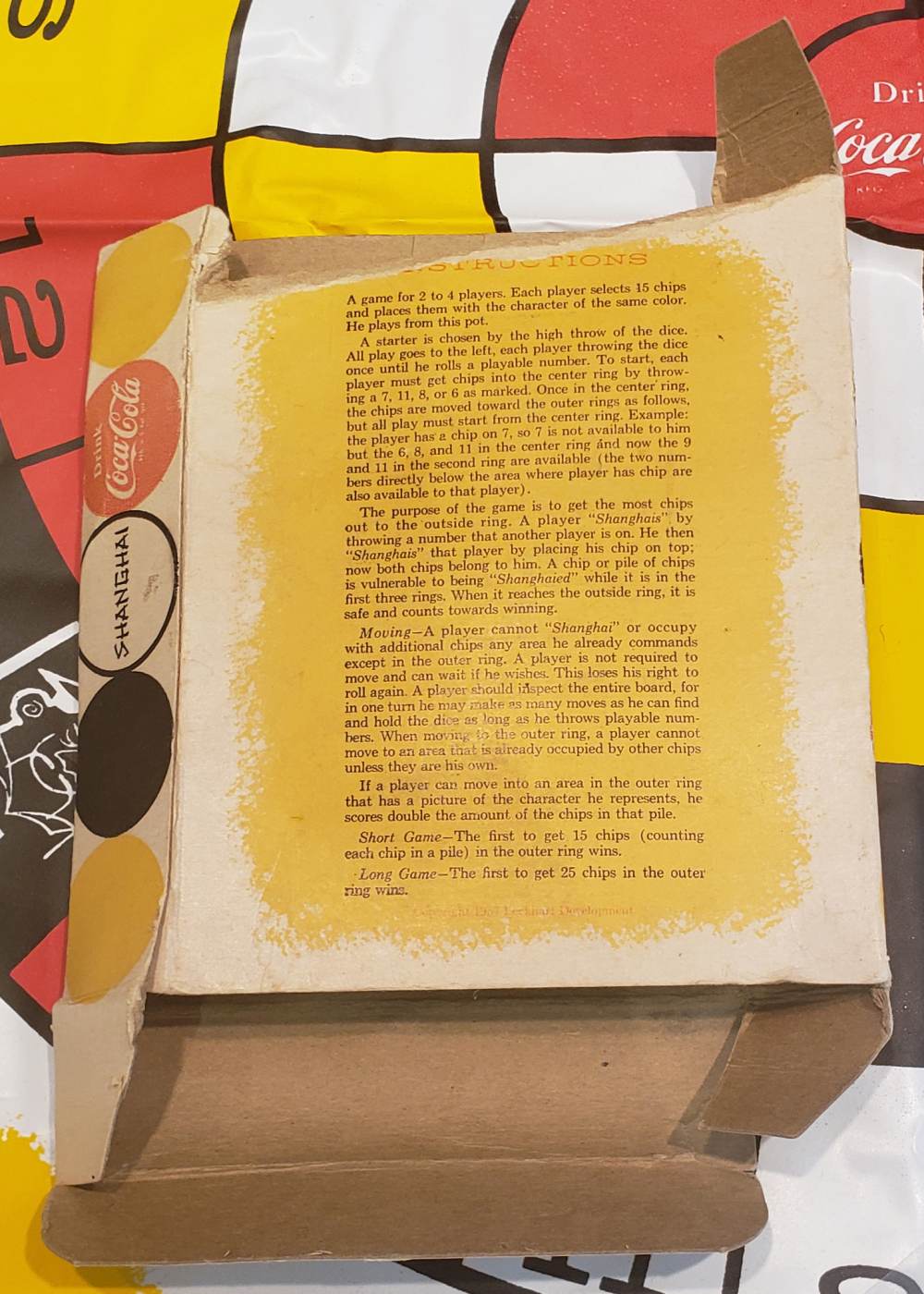

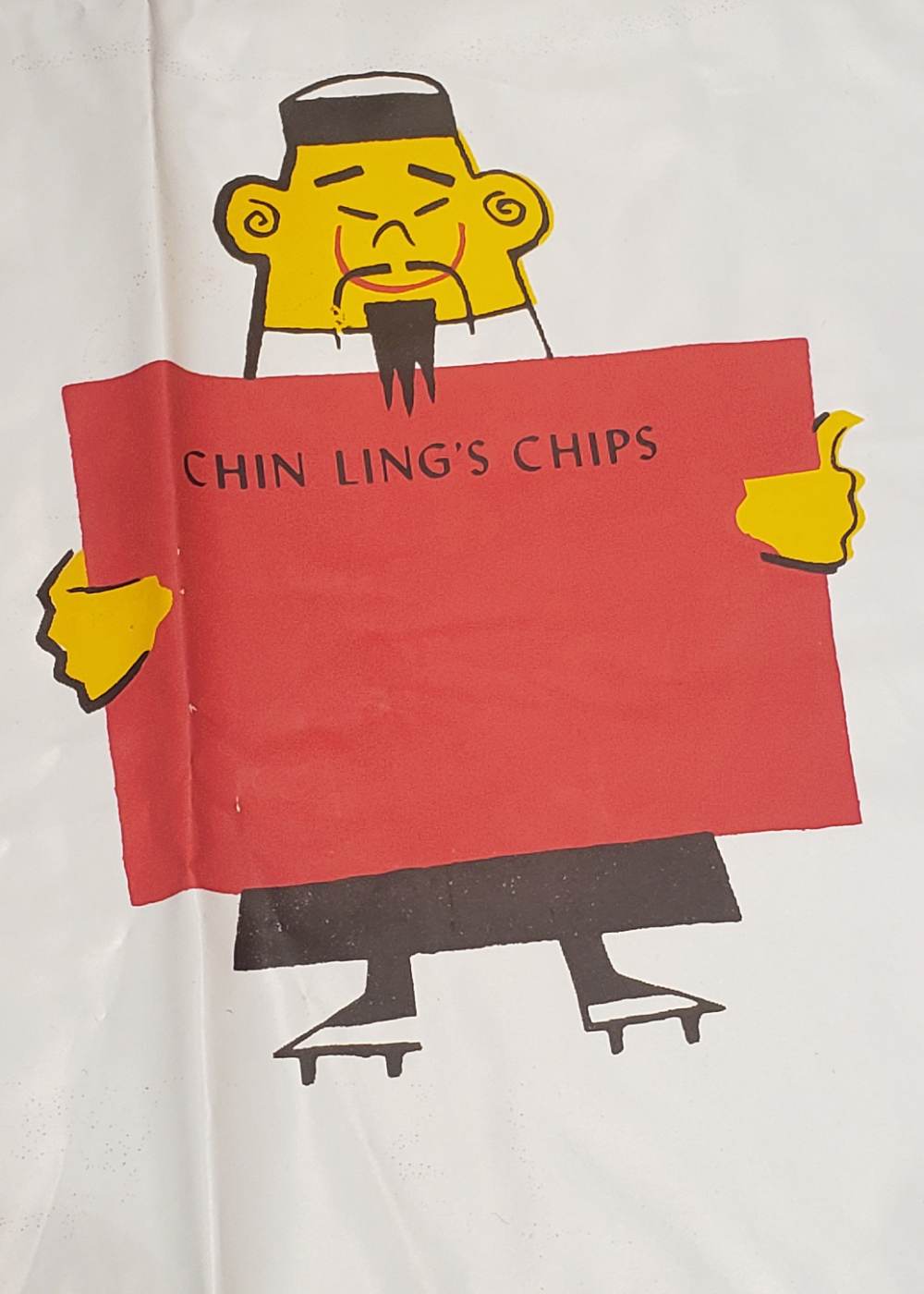

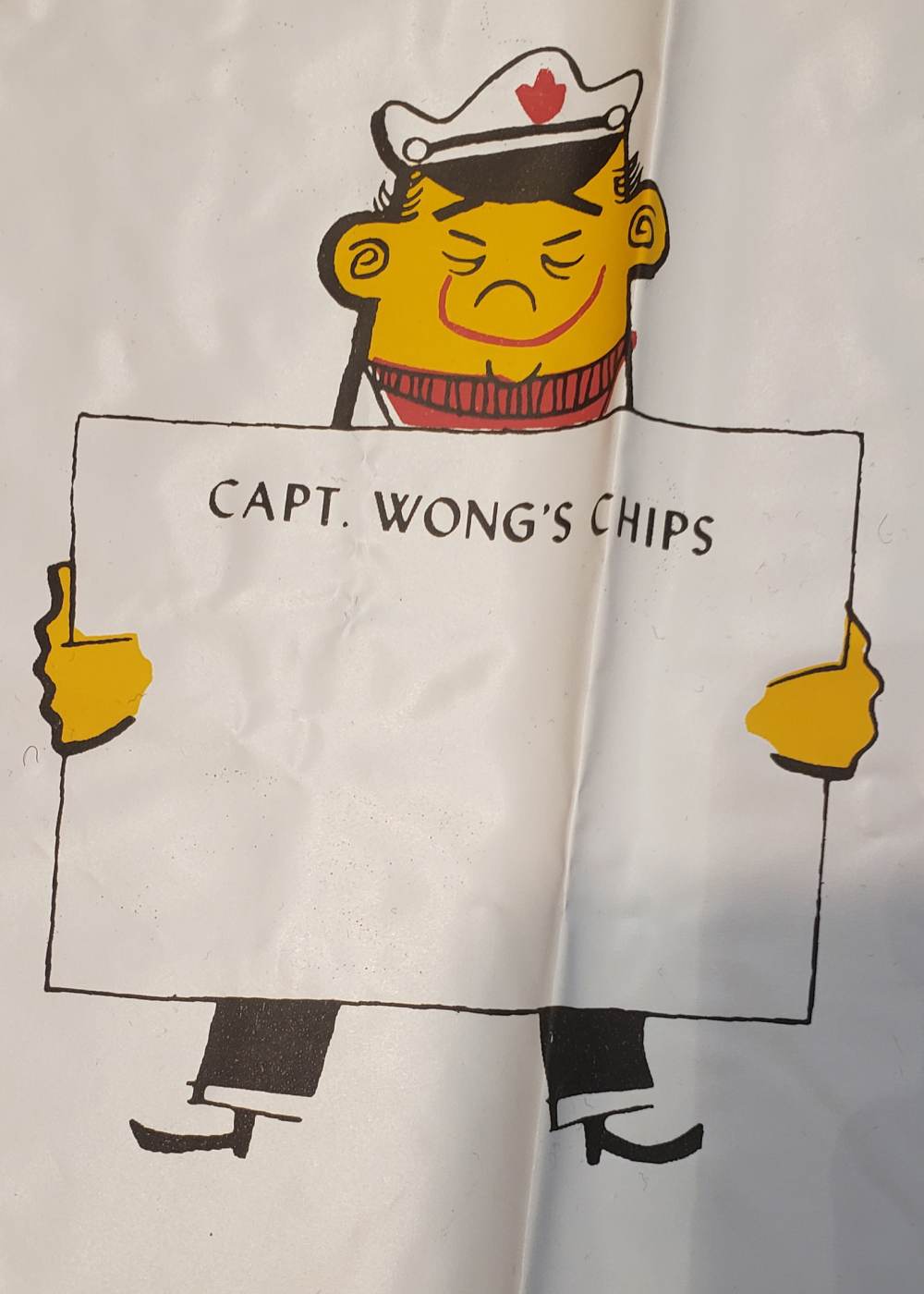

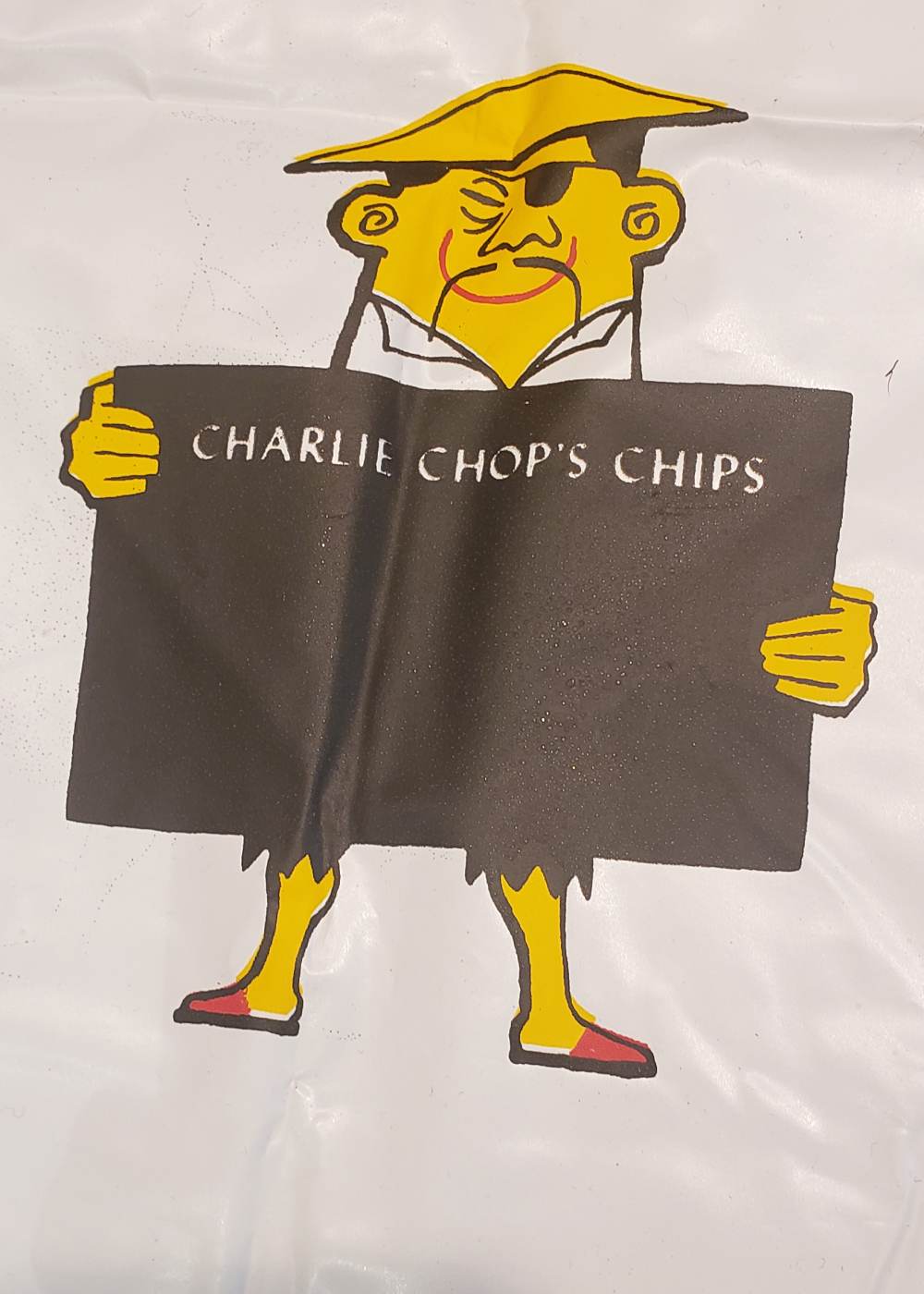

This week, we feature a Coca-Cola Company advertisement board game called Shanghai, with game mechanics revolving around capturing your opponent’s game pieces and scoring points with good dice rolls. This item was generously donated by Roy Delbyck, one of our MOCA Board Officers and a pretty regular donor of interesting materials relevant to our mission here at MOCA.

Upon looking at the board game box, one might think that it is simply a game that has a Chinese theme to it, but there is a little more to it than that. There is an underlying meaning behind the word “Shanghai” and we will be exploring that and how the game is related to the term. Before we get into the historical context of the word and how it ties to the game, let’s take a look at the contents of the game and its rules.