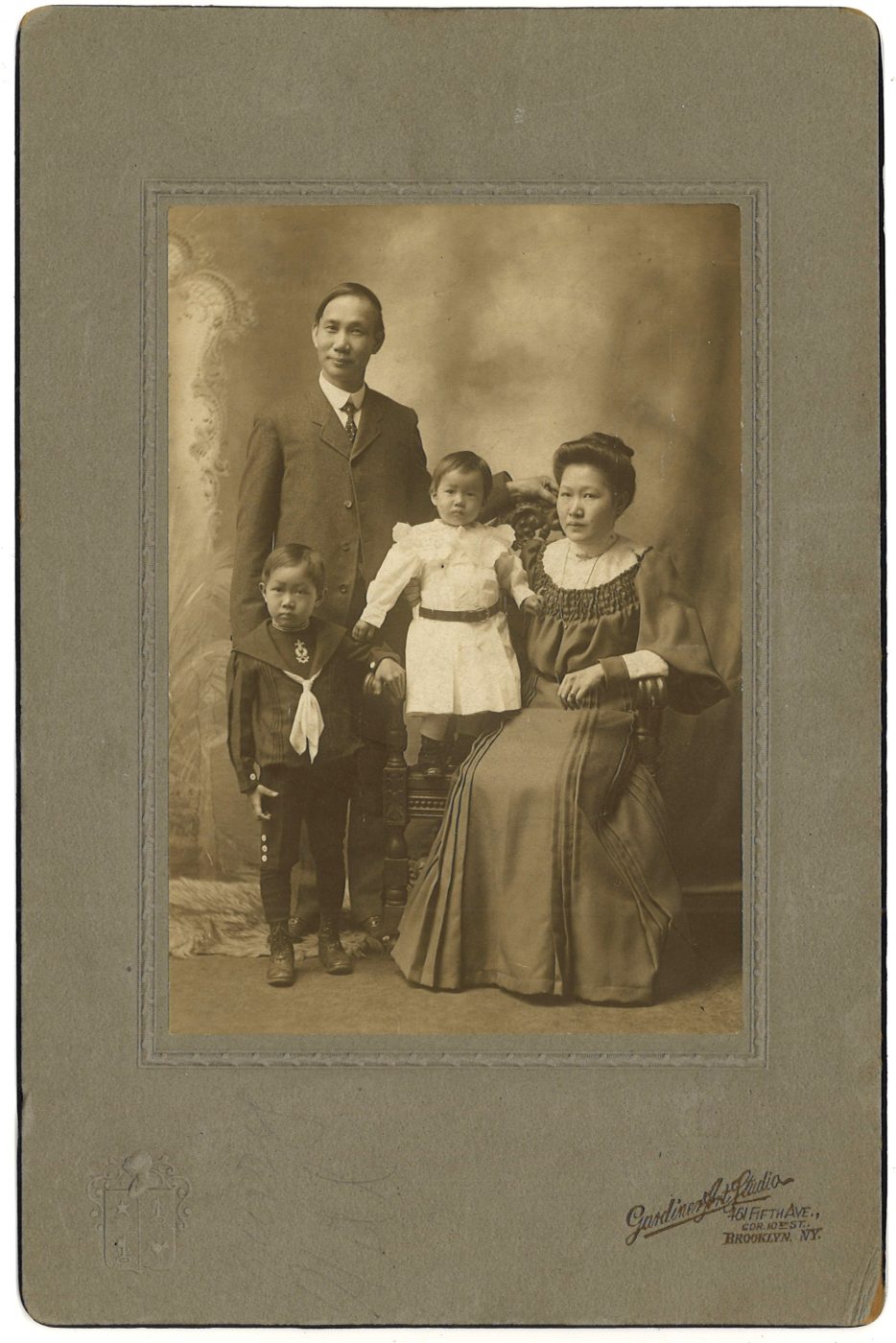

The woman captured in these family photographs was known simply to the donor of this collection as his great-grandmother, but recent scholarship by Cathleen D. Cahill has rediscovered that, for a brief moment, she was one of the most famous voices and faces in the American women’s suffrage movement. In 1912, rumors that a newly forged Republican China would soon recognize Chinese women’s right to vote flew across the Pacific and prompted leading suffragettes in New York to urgently seek out feminists in Chinatown. Accepting the invitation to speak with the white suffragettes were some of the few women legally allowed to immigrate to the U.S. under Chinese Exclusion: Grace Typond, wife of a community leader and merchant; Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, daughter of a Baptist minister and the first Chinese woman in the United States to earn her doctorate; her mother Lee Lai Beck; and Pearl Mark Loo, a teacher and missionary in her own right. (Women made up 0.05% of the Chinese population in the U.S. at the time of the 1900 census). Whereas white suffragettes aimed to capitalize on Chinese women’s accomplishments to shame the U.S. for lagging behind a nation perceived to be less modern and enlightened as China, Grace, Mabel, and Pearl used the unexpected platform to speak out against racial prejudice, educational inequality, and other pressing issues facing their community. In 1912, when suffragettes held what at the time was reported as the largest demonstration for women’s voting rights in history, Mabel took center stage on horseback as the head of the massive parade, and Grace likely marched with fellow Chinese women, who, though deemed “aliens ineligible for citizenship” because of their race, nevertheless actively supported more equitable citizenship rights for American women.

Douglas J. Chu’s family spans more than four generations in the United States and the branches of his family tree include many remarkable women. Among those who were recorded was Moy Han Ying (1868-1945), who immigrated to the U.S. with her husband in 1893. Han Ying held the distinction of being the only woman in her generation in NYC Chinatown who was able to read and write, and as such, organized English classes for Chinese at the YWCA once at 24 Pell Street. Also recorded was Adelaide Young (maiden name Su Lin Chen), who wrote firsthand accounts of her adventures as the first Chinese woman explorer of the Tibetan Himalayans for the North China Daily in 1934, when she accompanied her husband’s expedition to capture an Impeyan pheasant, described as one of the most beautiful pheasants in existence and never before captured alive by a collector or scientist. She also lent her Chinese name, Su Lin—which meant “a little bit of something very cute”— to the first live panda brought to the United States in 1936.

To watch Douglas J. Chu’s family home movies, please click on the following YouTube links: Typond Old Home Movie Brooklyn 4 winter Chinatown, Typond Old Home Movie Brooklyn 2, Typond Old Home Movie Brooklyn 3.