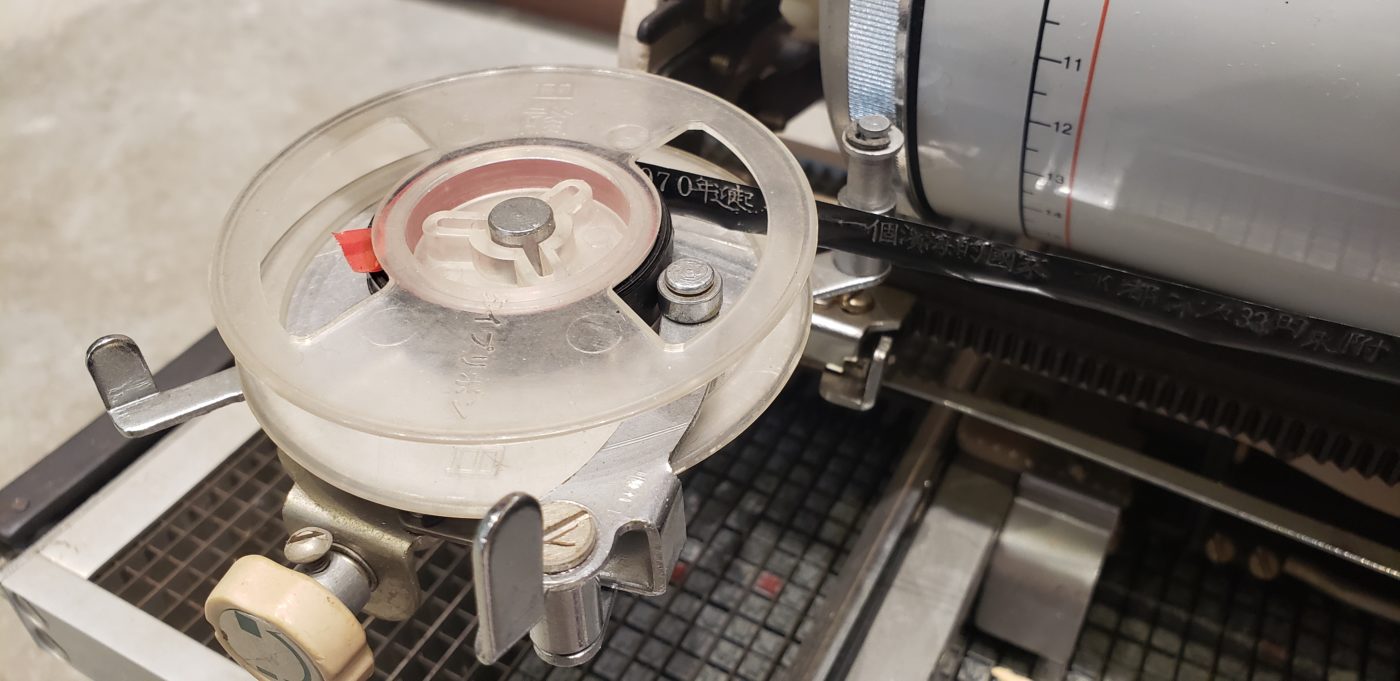

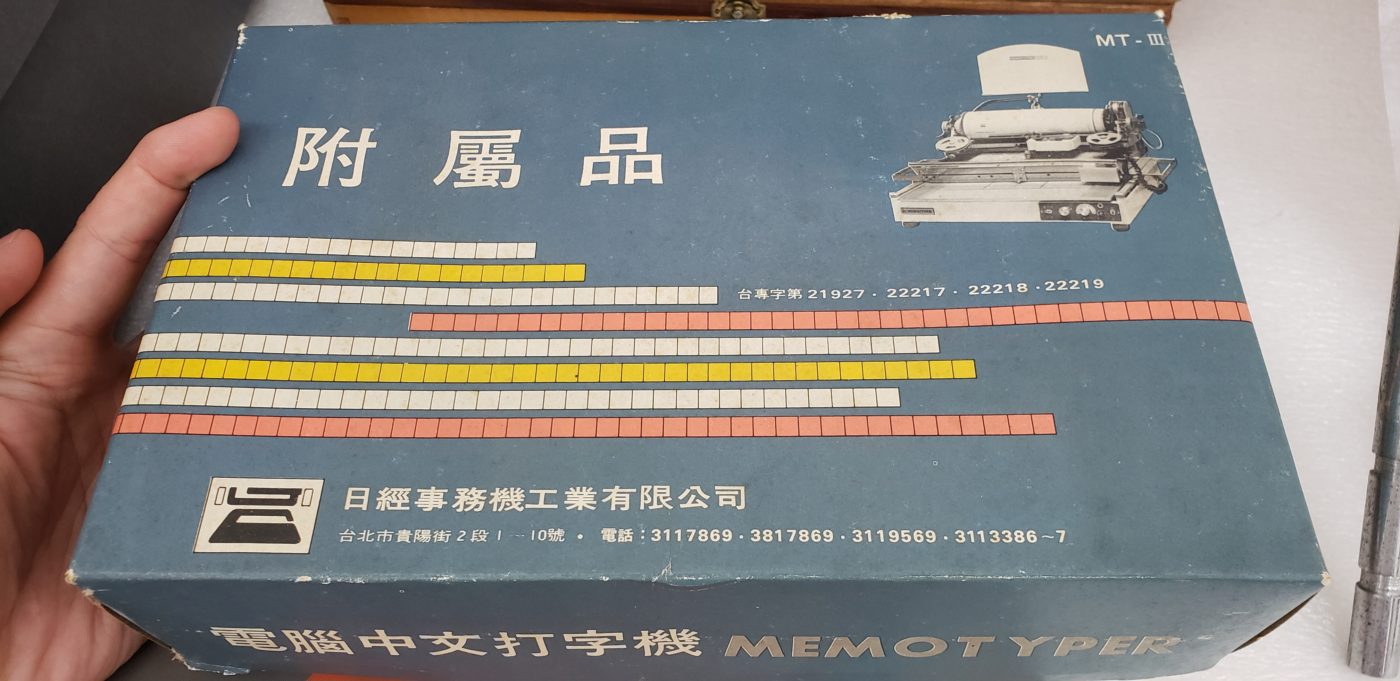

This week we feature a Chinese typewriter with movable character slugs donated by Mr. Fen-Dow Chu. The Jue Shine (Chine) typewriter is an advanced typewriter and possibly one of the final evolutions of the Chinese typewriter before computers and the QWERTY keyboard replaced these heavy mechanical wonders.

Weighing over 50 pounds and measuring 20 x 27 x 12 inches, the Jue Shine typewriter made its way overseas from Taiwan as a souvenir purchased by Fen-Dow Chu. Chu developed a fascination with typewriters and letter printing from a young age, having lived in Lanzhou with his father who oversaw the operations of a printing press. Although he would eventually move away to Taiwan and later on to the United States, he would retain vivid memories of his time in China and his interest in printing and typewriting. It was during a visit to Taiwan about 35 years ago that Fen-Dow would encounter a brand-new Taiwanese typewriter for sale and purchased it to bring back to the U.S.A.

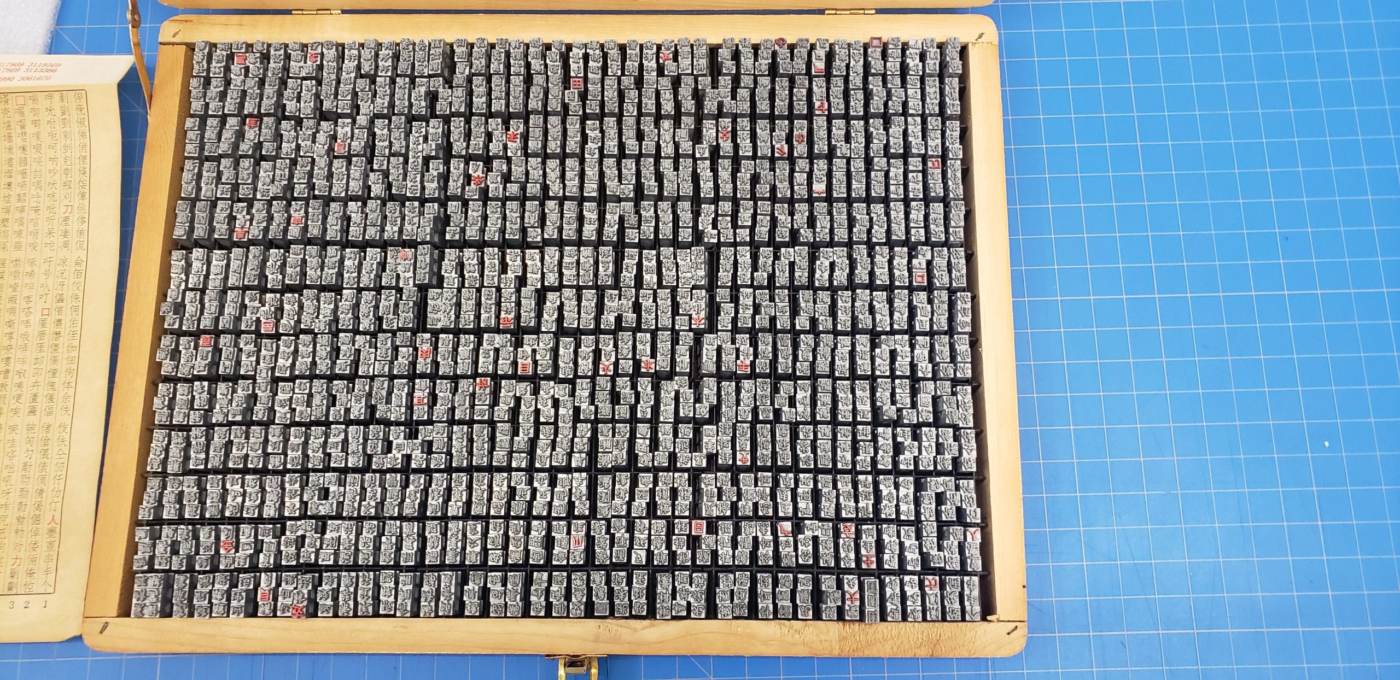

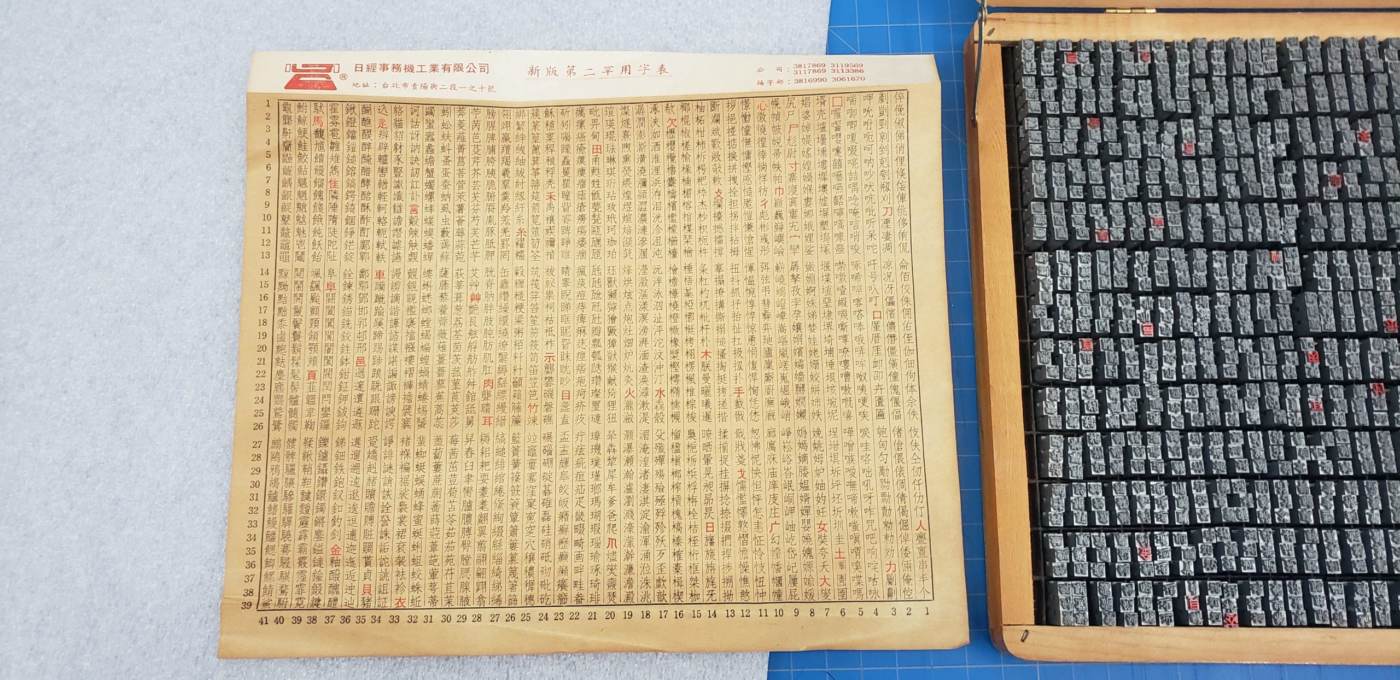

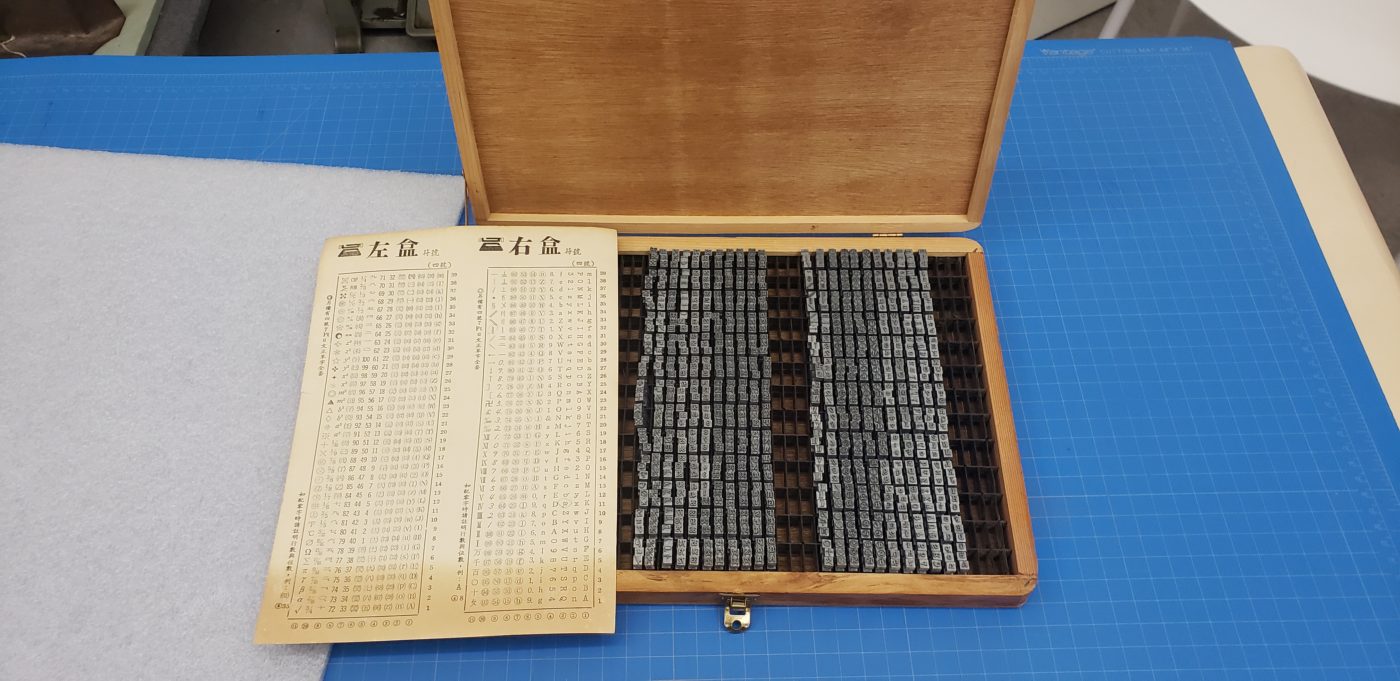

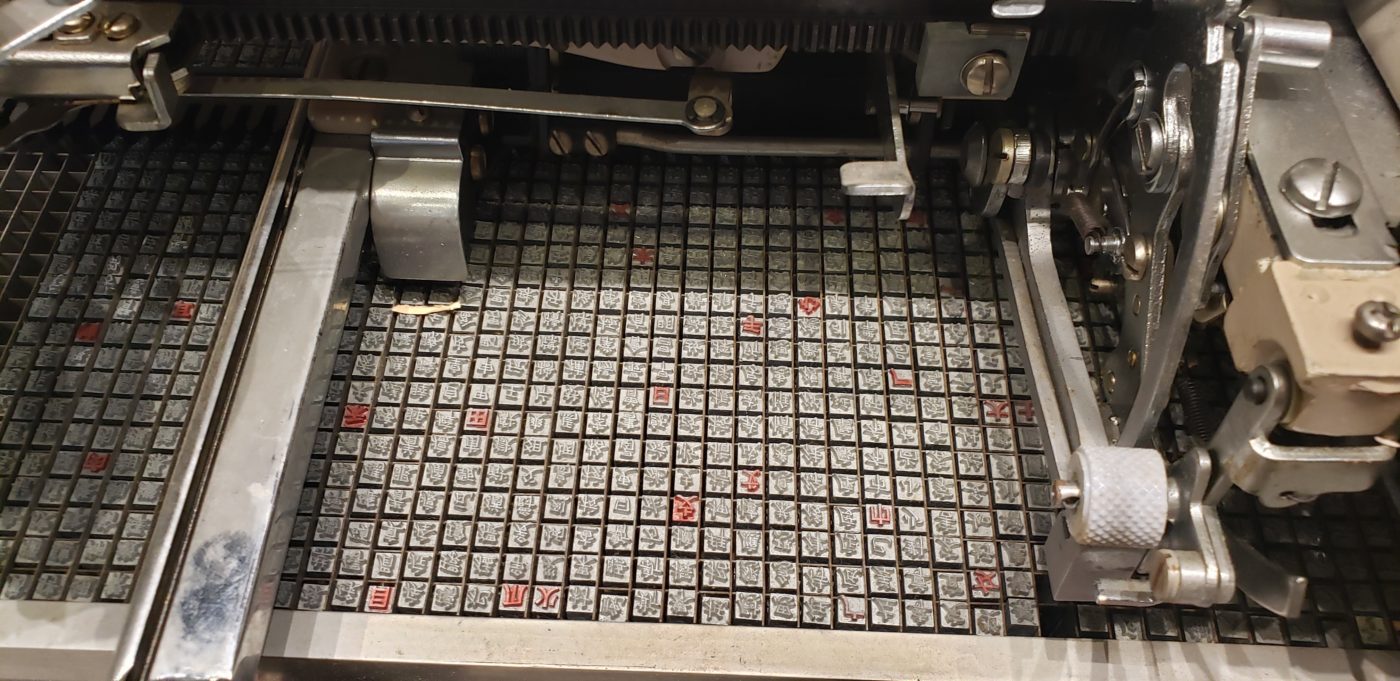

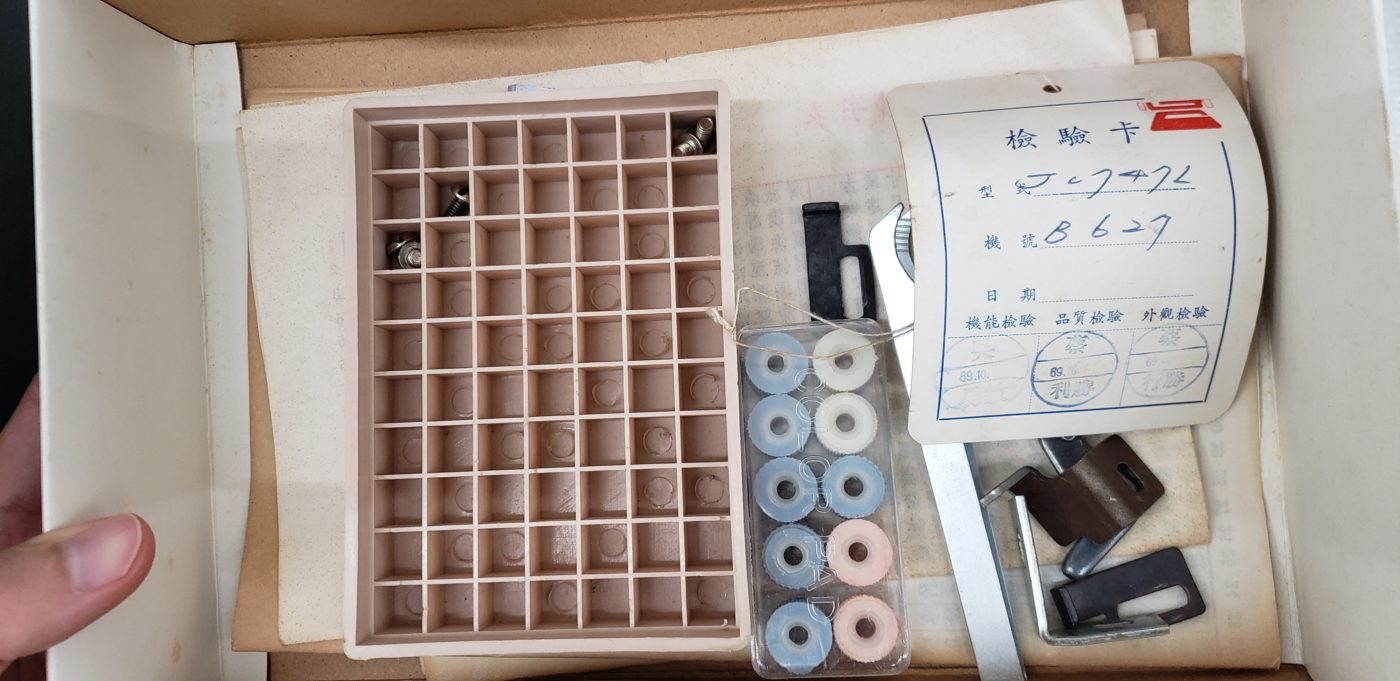

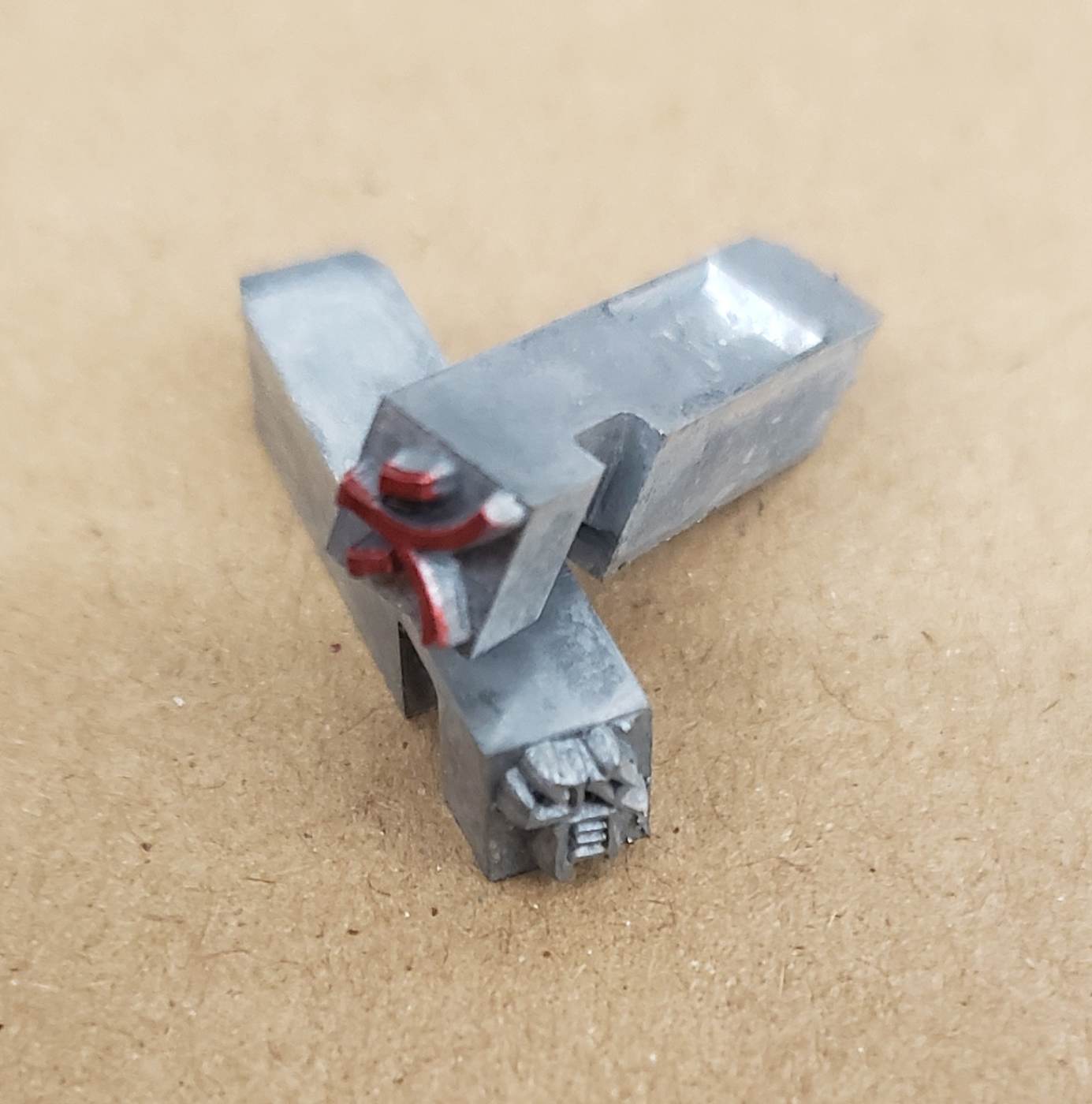

It has now made its way into the MOCA collections archives and would serve as a historic example of the complicated processes necessary to put Chinese characters onto paper before computer type became accessible. In addition to the large and heavy typewriter, the collection also includes four sets of metal type “slugs”, which are essentially rectangular blocks about one inch long, with characters carved onto the short end of one side. Typically, the slugs would be grouped based on what the typesetter would determine as common phrase combinations to cut down on the time needed to navigate the large type tray. For example, an article about a car would give the typesetter clues as to what combination of words would be most common, such phrases can include “horsepower”, “engine”, and “safety” which can be prepared beforehand in the character tray in the same general cluster.

In the early inception of the idea of introducing Chinese into typewriting, there were two competing systems with different approaches to how to put Chinese onto typewritten paper. The system of combining Chinese characters from a type tray into full sentences is attributed to Zhou Houkun, an MIT graduate of 1915 who designed a prototype that made use of only 3000 Chinese characters that he determined to be words that are used most commonly in everyday life. This is in contrast to another system developed by Qi Xuan, who, inspired by English and its use of alphabets to spell out words, suggested a system of using broken-up Chinese characters that can be modularly combined to create a whole word. Ultimately, Zhou’s design would be acquired by the Commercial Press in Shanghai and win over his counterpart’s design. His prototype would be refined by a Chinese Engineer named and sold as the first mass-manufactured typewriter.