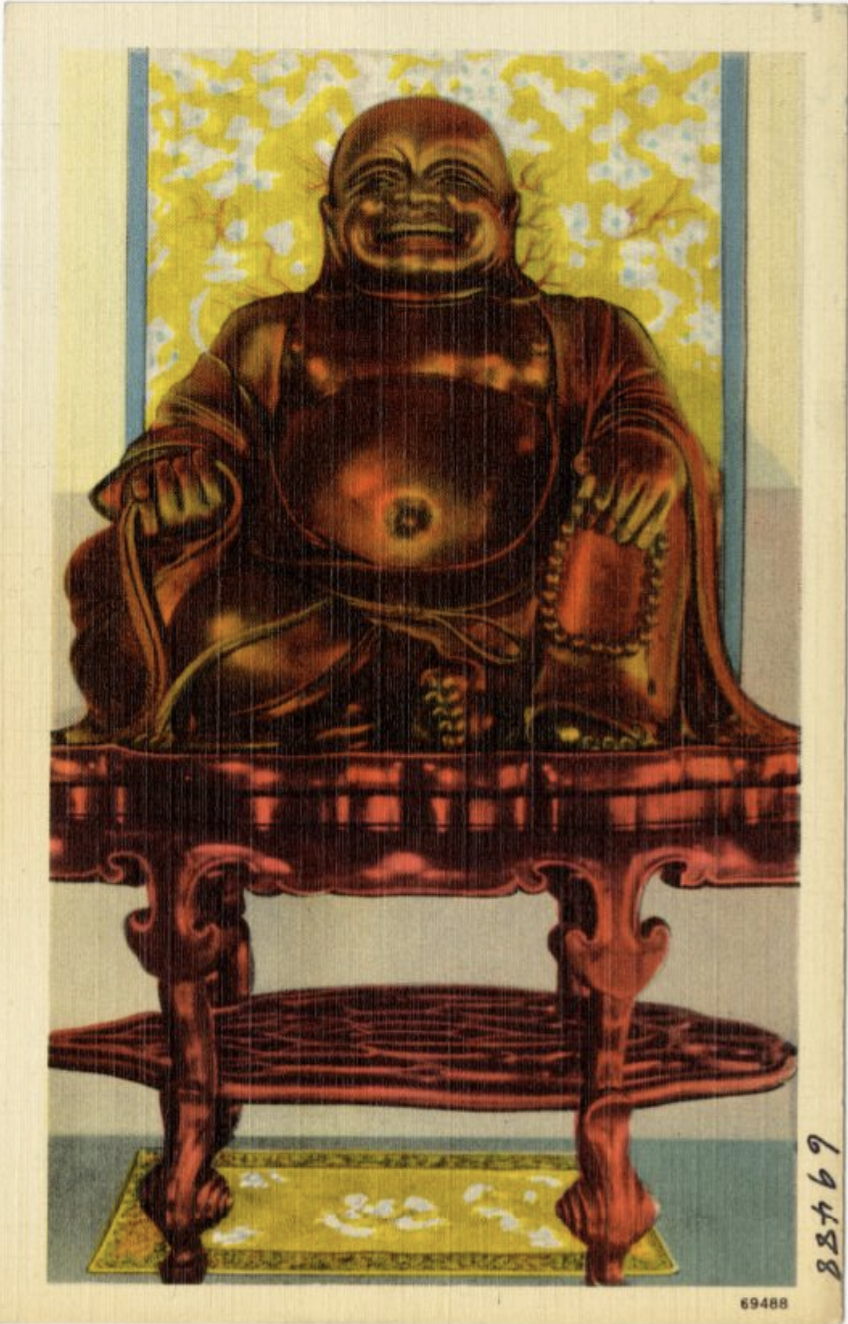

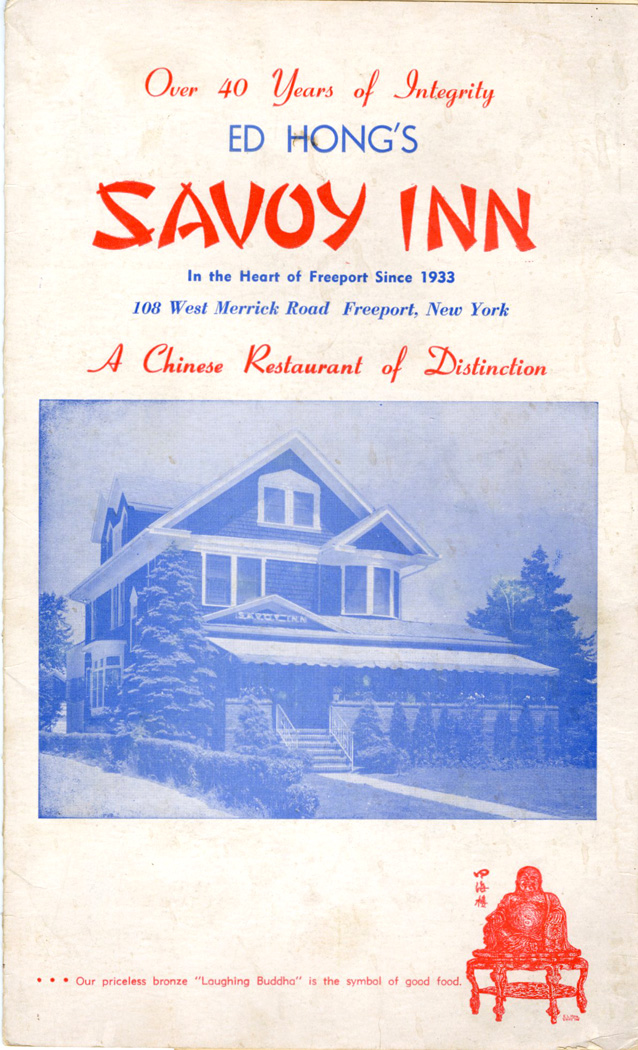

This bronze Laughing Buddha sculpture was an iconic piece of interior decor at the Savoy Inn, a Chinese restaurant that Edward Lim Hong opened in Freeport, Long Island in 1933. Over the 40+ years that the Savoy Inn was in business, customers rubbed the Buddha’s big toe for good luck, polishing the figure’s otherwise aged patina to a bright gold in that one spot. The provenance of the Laughing Buddha is uncertain, but a promotional postcard printed for the restaurant, shown below, claims that it was originally from Lung Shan Temple in Hong Kong, and over 200 years old.

One of the earliest articles in which the Savoy Inn’s proprietor appears—the New York Amsterdam News of July 20, 1935—informs us that Hong was a college graduate from Chicago managing the first Chinese food roadshow held in Freeport that summer. Hong was reportedly introducing locals to such Chinese culinary delicacies as “sharks’ fins that go to form a dish fit for emperors; birds nests found only in the Malay Peninsula and imported into China for soup; [and] duck eggs preserved in such a way that they can be kept for ages.” Like many of his college-educated Chinese American peers, he may have faced employment discrimination and consequently had few options outside of the restaurant industry. However, he seemed to have possessed enough resources to open what eventually became a white tablecloth establishment catering predominantly to the middle and upper classes. The name of his restaurant perhaps sought to evoke the 18th century’s newly minted Savoy monarchy in modern-day Italy, whose palace interiors were famously influenced by Chinese motifs and techniques (chinoiserie).

Since 1933, the Savoy Inn provided not only fine dining but also a regular meeting space for local civic and business groups, particularly women’s organizations. These included the Women’s Club of Massapequa, Long Island; the Freeport Auxiliary to South Nassau Communities Hospital; the Business Women’s Club of Freeport; and the South Shore Section of the National Council of Jewish Women, which held a Chinese luncheon and mahjong party at the Savoy Inn in 1944. Local support and fundraising for the war against Japan in China and World War II seemed to have opened opportunities in local society for Hong to be accepted and lead. In 1943, he was appointed chairman of the advance gifts committee of the National War Fund Drive, and as such, on occasion donated an entire day’s earnings from his restaurant to that organization. In 1945, he became the first Chinese merchant on Long Island to head a service organization when he became president of the Freeport Lions Club. He was also an invited speaker on topics related to China at local church clubs and civic organizations.

There seemed to exist some ties between Freeport industry and China, perhaps forged during wartime. This included Freeport’s Columbian Bronze Corporation, whose foundry was contracted by China to produce marine equipment as late as 1949. Chinese dignitaries such as General Peter Mow and Dr. C. F. Hsia, both delegates to the UN, were reported to have dined at the Savoy Inn in 1949, as did Madame Chiang Kai-shek and the representatives of 60 Chinese organizations in the New York Metropolitan area at a luncheon organized by the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association in 1952.

This Laughing Buddha, along with the postcards and menu shown below, helps MOCA illustrate and tell a fascinating local story of adaptation, as Chinese Americans built lives and opened Chinese restaurants not only concentrated in urban Chinatowns but that also fanned out across disparate communities in the United States.