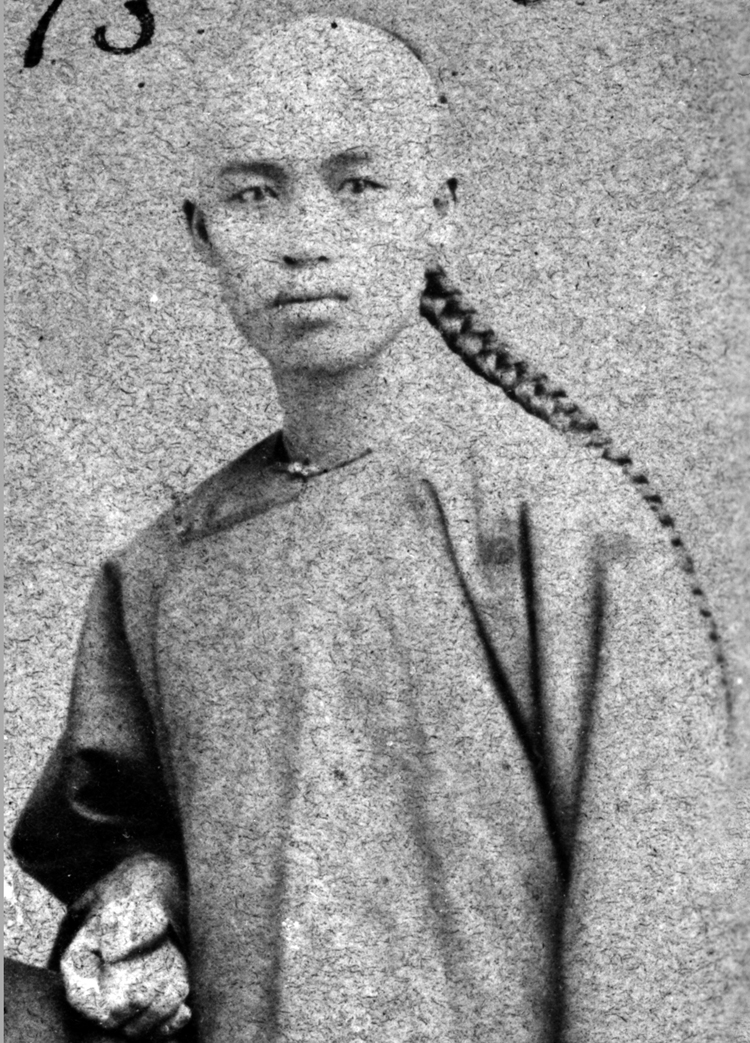

Ah Quin (1848-1914) was an exceptional figure during the early days of Chinese immigration to the U.S. He kept a journal and as a result left behind a wealth of firsthand accounts about life during that time. Born in Guangdong, Ah Quin received an English mission education in Canton before being sent to California by his family in 1868. He worked a variety of odd jobs including houseboy and cook across San Francisco, Santa Barbara, and Alaska, continuing his religious studies and learning merchandizing along the way. In Alaska, Ah Quin cut off his queue, marking his commitment to making America his home.

Ah Quin’s education and bilingualism opened many doors for him: he worked as a labor broker for the California Southern Railroad in San Diego for five years before branching out into merchandising and real estate. He became a respected leader within the San Diego community, earning him the unofficial title of “Mayor of Chinatown.” Between 1877 and 1910, Ah Quin kept a lengthy diary spanning ten journals in which he described his daily life, largely in English. In addition to these written records, the Quin family has maintained a strong oral history of Ah Quin’s life throughout the generations. Ah Quin’s legacy not only richly portrays the experience of Chinese in America around the turn of the 20th century, but demonstrates the importance of social and personal memory in preserving marginalized histories.